Cooper Grace Ward has been announced as the winner of four categories in the latest Beaton Client Choice Awards: Best Australian Law Firm, Best Professional Services Firm, Most Innovative Law ...

In the recent case of Knight Frank Australia Pty Ltd v Paley Properties Pty Ltd [2014] SASCFC 103, a $1.5 million purchase contract was signed by only one director of the purchaser. The company had two directors.

The issue was whether there was an enforceable contract with the purchaser and, if the contract had not been correctly signed by the purchaser, whether the director who purported to sign the contract on behalf of the purchaser was personally liable to pay damages to the vendor for breach of warranty of authority.

The background to the case

Under sections 126 and 127 of the Corporations Act 2001, a distinction is drawn between execution by the company itself (which is governed by section 127), and execution by an agent on behalf of the company (which is governed by section 126).

Section 127 provides for execution of a document with or without using the common seal. When the common seal is not used and where a company has more than one director, section 127 requires that at least two directors or a director and a company secretary of the company sign a contract in order to bind the company.

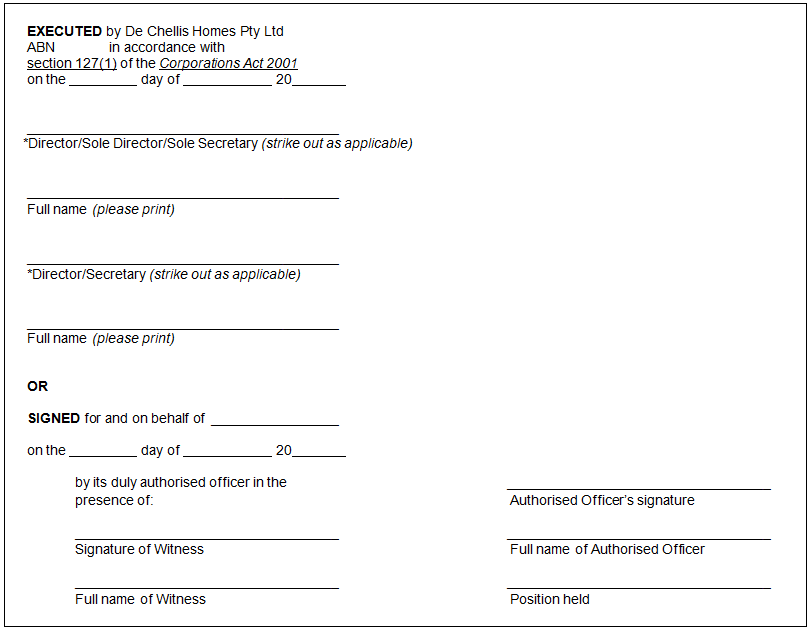

The contract execution page for the purchaser (De Chellis Homes Pty Ltd) was material to the Full Court’s analysis. There were alternative execution boxes for the purchaser:

The purchaser’s execution page proceeded upon the same distinction between execution by the company itself – which was provided for in the first execution box – and execution by an agent on behalf of the company, which was provided for in the second execution box.

The first execution box stated explicitly that the execution was in accordance with section 127. It made provision for execution by the company in two different modes, depending on whether the company had one or more directors:

Section 126 provides that the power of a company to make a contract may be exercised by an individual acting with the company’s express or implied authority on behalf of the company. The second execution box provided for execution by an agent on behalf of the company.

The purported execution by the director

The director of De Chellis Homes signed in the first execution box as a director and he struck out the words ‘Sole Director/Sole Secretary’, designating that the company had two or more directors.

In the absence of a second signature by a second director it was clear on the face of the execution page of the contract that it had not been executed by the purchaser under section 127.

The second execution box for execution by an agent on behalf of the company was left blank with no alterations.

The purchaser’s constitution

The purchaser’s constitution was also relevant. It provided that where the company had more than one director and the Board of directors resolved that a director specified in that resolution was authorised to execute documents, then the company could execute any document by that director signing the document.

There was no resolution authorising the director to execute the contract on behalf of the company.

However, if he had been signing the contract in accordance with such a resolution, he would have signed the second execution box as agent on behalf of the company because the execution would have been under section 126 and not under section 127.

The vendor was also unable to place any reliance upon section 129 of the Corporations Act, sometimes referred as part of the ‘indoor management rule’.

The specific assumptions in issue were subsections 129(5) and (6). Generally speaking, subsections 129(5) and (6) entitle a person dealing with a company to assume that a document has been duly executed by the company if the document appears to have been signed in accordance with section 127.

In this case the contract did not appear to have been signed in accordance with section 127 at all, because the execution page indicated that the director was not the sole director and a second director or secretary had not signed as representing the company.

The purchaser had not correctly signed the contract and, as a result, the contract was not enforceable against the purchaser.

Was there a breach of warranty of authority by the director of the purchaser?

The Full Court reiterated the well-established legal principle:

If an agent purports to enter into a contract on behalf of a principal, purportedly within the scope of the agent’s authority, and the other party relies upon the agent’s representation of authority to enter into the purported contract with the principal, the agent warrants that the agent has authority to enter into the contract. The agent is liable for damages to the other party for any breach of that warranty of authority.

The director had a lucky escape.

The Full Court said the following:

Comments

Correctly signing a contract by or on behalf of a company is not a mere formality.

If a contract is incorrectly signed on behalf of a company it may result in the contract being unenforceable against the company. Worryingly for the director or agent who purported to sign the contract on behalf of the company, they might be personally liable.

The assumptions in section 129 of the Corporations Act are technical in their application. Whether a particular assumption will apply will depend on the facts.

Where a contract is purported to be signed by an agent or representative on behalf of a company (as opposed to the situation where a contract is signed by the company itself) there will be a red flag as to whether the purported representative or agent has authority to sign on behalf of the company.

If you are the other party to a contract you should obtain confirmation that the representative or agent had authority to sign on behalf of the company.

In internal company disputes or where there is ‘seller or buyer remorse’, allegations are commonly made that a representative of the company acted without authority in purporting to sign an agreement.

The warning for a person purporting to sign as representative or agent on behalf of a company is that they can be liable to pay damages if they breach the warranty that they had authority to sign on behalf of the company. They should make sure that they have written evidence of the required authorisation before purporting to sign on behalf of a company.

This publication is for information only and is not legal advice. You should obtain advice that is specific to your circumstances and not rely on this publication as legal advice. If there are any issues you would like us to advise you on arising from this publication, please let us know.

Subscribe to our interest lists to receive legal alerts, articles, event invitations and offers.

In this edition of It depends, family partner Justine Woods discusses whether you can safeguard an intergenerational family business from a family law claim. Video Transcript Hello. Hello, everyone. ...

Cooper Grace Ward acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future Traditional Custodians and Elders of this nation and the continuation of cultural, spiritual and educational practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Fast, accurate and flexible entities including companies, self-managed superannuation funds and trusts.